The full informed consent

Welcome to The Full Informed Consent(!), a blog explaining the unstated risks related to child mental healthcare and child psychiatry. These brief articles, which drop every few weeks, help parents and adults caring for children interrogate standardized practices in child mental health. Each article includes a parenting tip families can apply to their children’s mental healthcare to ensure it is careful and full of care, rather than careless and full of harm. If you’re a member of the community and interested in a particular topic not covered here, please reach out to Rupi Legha MD directly via email (rupi@rupileghamd.com).

Parents and families deserve the full truth. Child mental health providers are obligated to give them the full informed consent. The Full Informed Consent strives to provide both.

When Protection Becomes Punishment: Why WE NEED TO MOVE FROM REPORTING TO SUPPORTING

What if the systems meant to protect families are the very ones causing them harm? In her latest Health Affairs essay, Dr. Rupi Legha challenges the assumption that surveillance equals safety and introduces a new vision of care—one rooted in trust, compassion, and equity. Through the lens of “mandated supporting” and her Protective Care framework, she calls on clinicians to move from reporting to supporting—and to reimagine what true protection could look like.

LA County’s $4B Settlement Exposes the Truth: Mental Health Must Stop Feeding the System

LA County’s $4 billion child welfare settlement exposes decades of systemic abuse—and the complicity of healthcare in fueling that harm. In this piece, psychiatrist Dr. Rupi Legha examines how mandated reporting often reinforces racial injustice and why mental health providers must embrace mandated supporting to truly protect children and families. A must-read on ethics, equity, and the future of trauma-informed care.

Psychological Safety as Structural Safety: Rethinking Professionalism, Competency, and Mental Health in the Workplace

Psychological safety has become a buzzword — often reduced to “feeling heard” or building trust on teams. But real psychological safety isn’t soft. It’s structural. It’s shaped by racialized definitions of professionalism, legacies of exclusion, and systems that punish distress while performing care.

This isn’t just about culture — it’s about power.

Who gets protected.

Who gets punished.

And who is never safe at all.

From Compliance to Clinical Defiance: A Vision for Liberatory Child Mental Healthcare

What if mental health care for children wasn’t about fixing them—but about freeing them?

Too often, the systems that claim to protect—child psychiatry, education, child welfare, juvenile justice—are rooted in punishment, compliance, and control. Even when we don’t directly participate in that harm, as providers we are still entangled in it. We document. We diagnose. We sometimes report.

But what if we told the truth? What if we saw resistance not as pathology, but as survival? What if we stopped asking children to bend to broken systems—and began rebuilding those systems for their liberation, their dignity, and their joy?

In this piece, I reflect on what it means to practice clinical defiance in a carceral system. I share how “mandated supporting” allows us to interrupt harm, how rehumanizing documentation can serve as protection, and how naming the full risks of crisis care can be an act of love. Because love has never been the problem in our work—it’s the thing we’ve been told to leave at the door.

Let’s imagine something better.

Let’s build it—together.

Before You Say Yes: A Parent’s Guide to Navigating Mental Health Crises Without Harm

Before you say yes to hospitalization or police intervention for your child’s mental health crisis, pause. Schools, hospitals, and crisis hotlines often default to calling 911 or sending kids to the ER—but these interventions can introduce trauma, coercion, and harm, especially for Black, Brown, and neurodivergent children. Police involvement escalates risk, ERs rely on restraint and sedation, and psychiatric labels can misdiagnose distress as defiance. You deserve FULL informed consent. This guide walks you through the risks, alternatives, and proactive steps to navigate crises safely—because the system won’t inform you, but you can prepare now. Read more to learn how to protect your child before a crisis happens.

The Death of DEI: Mourning What Could Have Been, Building What Must Be

“Plantations were very diverse places.”

Ruha Benjamin’s words hit me like a brick. Diversity was never the measure of justice. DEI allowed institutions to claim progress without making real change—offering a cosmetic fix while leaving oppressive systems intact.

Now, as DEI initiatives are dismantled, I find myself mourning not just their failure but the loss of what could have been. Institutions promised transformation, yet racial health disparities persist, child health inequities worsen, and backlash against even symbolic progress is here.

Perhaps DEI’s demise is an opportunity. If we are done with performance, what do we build instead?

Holding Steady in the Storm: Staying Rooted in Antiracism During Chaotic Times

Holding Steady in the Storm: Staying Rooted in Antiracism During Chaotic Times

These are wild times. The attacks on DEI, trans rights, and affirming, antiracist care are relentless. And yet, I feel deeply grateful to have exited institutions in 2021—privileged to build on my own terms.

But staying steady in this storm? That takes intention.

Through my work in policy, scholarship, and clinical practice, I’ve honed key lessons:

🔹 Not everyone is the right collaborator—setting clear criteria for ethical, reciprocal partnerships.

🔹 Scholarship is resistance—pushing journals to include reviewers with lived experience.

🔹 Sustainability means overflow, not burnout—prioritizing care so I can pour into others with joy.

We are in wild, dangerous times. But we are also in a moment of great possibility.

How are you holding steady in the storm?

ANTIRACISM TODAY, ANTIRACISM TOMORROW, ANTIRACISM forever: Transforming Resistance into Progress

"Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" was famously declared by George Wallace during his 1963 inaugural address, embodying resistance to civil rights and systemic racism. Today, we reclaim and invert this phrase: Antiracism today, antiracism tomorrow, antiracism forever.

In the wake of the 2020 racial reckoning, antiracism efforts surged across sectors, yet backlash has been fierce. From attacks on DEI initiatives to legal challenges against equity-driven healthcare programs, the stakes are higher than ever. As marginalized communities face worsening disparities, we are called to resist, to rise, and to act boldly.

Antiracism is not optional—it’s essential. Together, we can create spaces where justice thrives, equity leads, and progress prevails.

Join us in this fight. Let’s turn resistance into lasting change.

From mandated reporting to mandated supporting: a 3-part video story

Reimagining Mandated Reporting: From Harm to Hope

Mandated reporting is meant to protect children—but for Black families and other racially minoritized groups, it often causes more harm than good. Nearly half of all children in the U.S. will be reported to Child Welfare by the time they turn 18, yet only a fraction of cases are substantiated.

In my latest series, I share the story of one family’s journey through this flawed system and how transparency, education, and antiracist care helped them navigate it.

✨ Let’s rethink how we protect families. Join the conversation and explore how we can transform mandated reporting into mandated supporting.

Brokering Transformative Conversations: Lessons from a Decade of Antiracism Speaking

Antiracism lectures aren’t just presentations—they’re transformative experiences. In my decade of speaking, I’ve learned how to create impactful, emotionally resonant talks that challenge systemic inequities while inspiring meaningful action. From navigating pushback to leveraging powerful imagery and modeling vulnerability, these lessons have shaped how I approach this intricate, taxing, yet deeply rewarding work.

In 2025, as we face persistent inequities and rising demands for justice, these conversations matter more than ever. As one student shared after a lecture: “This changed how I see the world.” Let’s continue pushing boundaries together.

2024 in review: A year of advocacy and growth

2024 in Review: A Year of Advocacy and Growth

This year, we reimagined mental healthcare as caring and healing, rather than coercive and pathologizing. Highlights include the upcoming publication of “An Antiracist Approach to Oppositional Defiant Disorder” in a top pediatrics journal, the successful pilot of our Antiracism in Mental Health Fellowship, and the expansion of my clinical practice to New Mexico.

Looking ahead to 2025, I’m excited to champion the SHIELD Act Campaign to mitigate police involvement in mental health crises, expand our Fellowship, and bring my holistic care approach to even more states.

Join the journey to transform mental healthcare!

Clinical Activism: Reimagining Professional Advocacy in Mental Healthcare

What if mental healthcare could move beyond managing symptoms and diagnosing conditions to address the root causes of suffering? Clinical activism does just that—it’s the intentional integration of advocacy, social justice, and transformative action into clinical practice.

Drawing on my experiences with patients and my work in grassroots advocacy, I’ve come to understand that true healing requires challenging systemic inequities, defending dignity, and empowering communities. From helping a survivor reconnect with her children to fighting punitive charges against a traumatized teen, clinical activism is about co-creating pathways to justice, safety, and liberation.

The Full Informed Consent: Transforming Mental Health Care through transparency and trust

Mental healthcare is often presented as a refuge of safety and support, with providers emphasizing adherence to the “standard of care” as a guarantee of quality. However, for racially marginalized communities, this standard frequently conceals significant harms. Families can find themselves blindsided and betrayed by a system they trusted to provide help, only to face inequities and systemic failures instead.

This is where full informed consent becomes vital—not just as a legal requirement, but as a transformative practice. By exposing hidden risks, acknowledging systemic inequities, and fostering collaboration, full informed consent restores trust and empowers families to navigate mental healthcare with clarity and confidence.

The Full Informed Consent: Your Mental Health Provider Does Not Have to Take Any Responsibility for Addressing Mental Health Inequities

Racism is a pivotal determinant of mental health, yet mental health providers are not legally required to address it in clinical care. Standard practice guidelines remain glaringly silent on racism, perpetuating harm to marginalized communities, especially Black individuals. This failure to confront systemic inequities is not just oversight—it’s deadly. The time for half-measures and empty apologies is over; mental health care must be trauma-informed and fundamentally antiracist.

The Full Informed Consent: The Mental Health System Is Broken—And Health Insurance Companies Are (partly) to Blame

We all know that mental health care is just as crucial as physical health care. In fact, the division between the two is artificial and counterproductive. Yet insurance companies continue to treat mental health care as an afterthought. Though federal law mandates equal access to mental and physical health services, my experience shows that insurance companies regularly deny or delay coverage for the person-centered psychiatric care I provide.

This shady behavior has devastating effects on patients, families, and mental health providers alike.

The Full Informed Consent: The Doctors Are Not Okay

The doctors are not okay, and the medical profession is not well.

The Full Informed Consent: The Unstated Legacy of Racism and White Supremacy in Child Mental Healthcare

Providers and health organizations alike encourage children and families to pursue mental healthcare as if it were universally healing. Amidst the pediatric mental health crisis–characterized by increased rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide attempts–”access to quality mental healthcare” remains the prevailing discourse. But what if child psychiatry was not originated or designed to protect and serve your children’s best interests. What if it refused to acknowledge the unique harms facing your child? What if it carried unstated risks of harm that are not accounted for in these general recommendations to pursue it?

The Full Informed Consent: Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) is the 21st Century Version of Drapetomania

ODD is a disruptive, impulse-control and conduct disorder characterized by at least four symptoms occurring in three categories of behavior: anger or irritability, being argumentative or defiant, and vindictiveness. Difficulty with rules and authority figures or adults is also a key feature. Black children are far more likely to be diagnosed with a disruptive behavior disorder like ODD than White children, even when these groups demonstrate similar externalizing behaviors. Children entangled in carceral settings, like juvenile detention or child welfare—most of whom are of color—are also more likely to carry an ODD diagnosis. However, treatment guidelines from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, do not account for these inequities at all. They recommend adult supervision, proper discipline, and parent training as primary interventions.

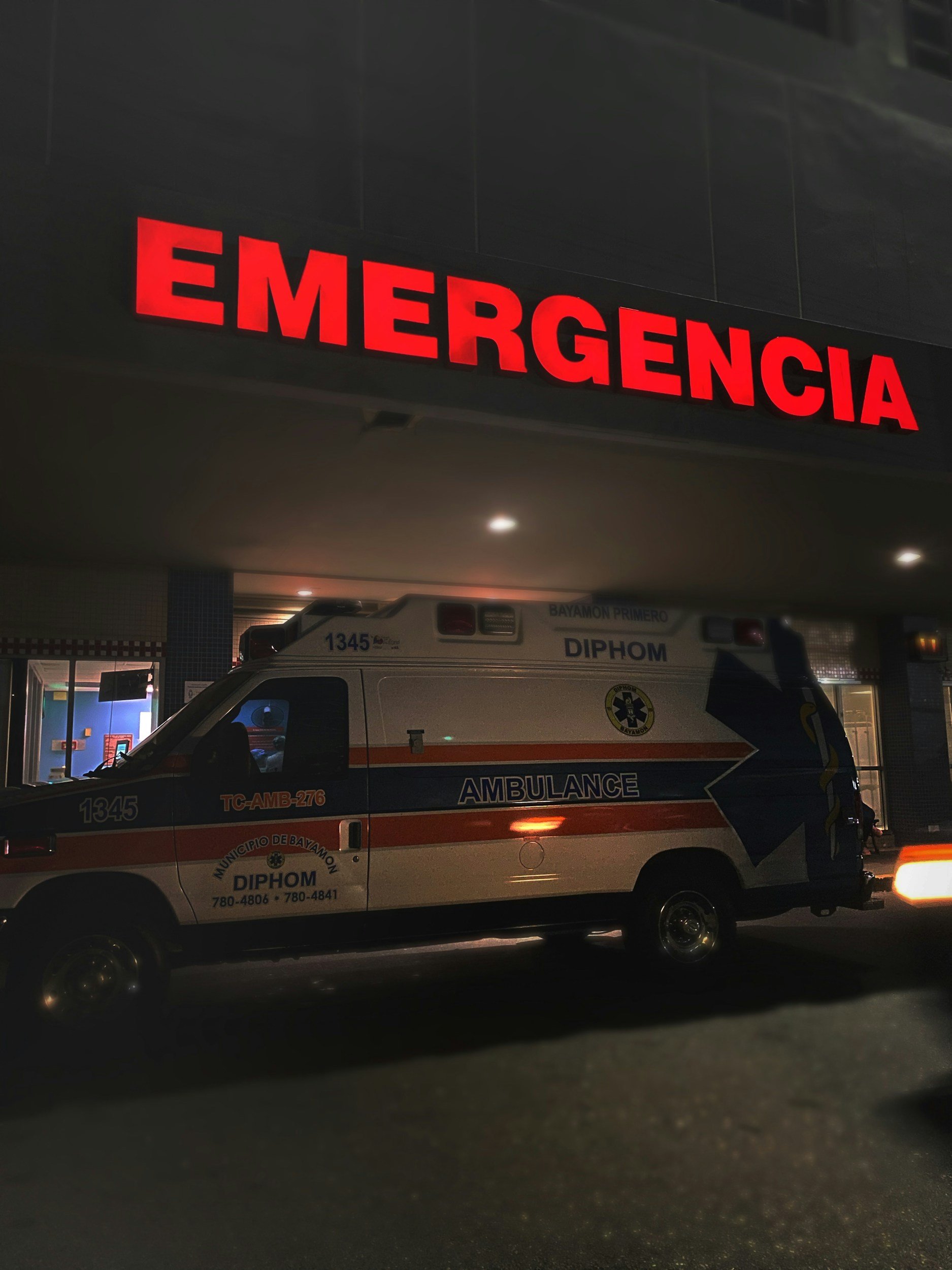

The Full Informed Consent: Visiting the Psychiatric Emergency Room

“If you or your child is having a psychiatric emergency, please hang up and call 911 or go to your closest emergency room.” Virtually all mental health providers feature this statement in their voicemail recordings. They also recite it when “safety” planning for acute psychiatric emergencies related to suicide, aggression, and other out of control behaviors. Prominent organizations like the National Alliance for Mental Illness and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists recommend these options as the surest way to promote safety and prevent further harm. But this unanimous messaging betrays the inequitably distributed dangers and harms embedded within the mental health crisis continuum of care.

The Full Informed Consent: Mandated Reporting to Child Protective Services (CPS) in Child Mental Health

Child mental health providers typically require parents initiating care to sign a “Notice of Privacy Practices” indicating that providers are mandated reporters legally required to report actual or suspected instances of abuse and neglect of a minor. Some providers might also explain the reporting mandate during an opening session. What is not often discussed, however, is what the reporting process looks like, how families and children are notified, and what if any responsibility providers take to protect families of color from reporting’s endemic racism.